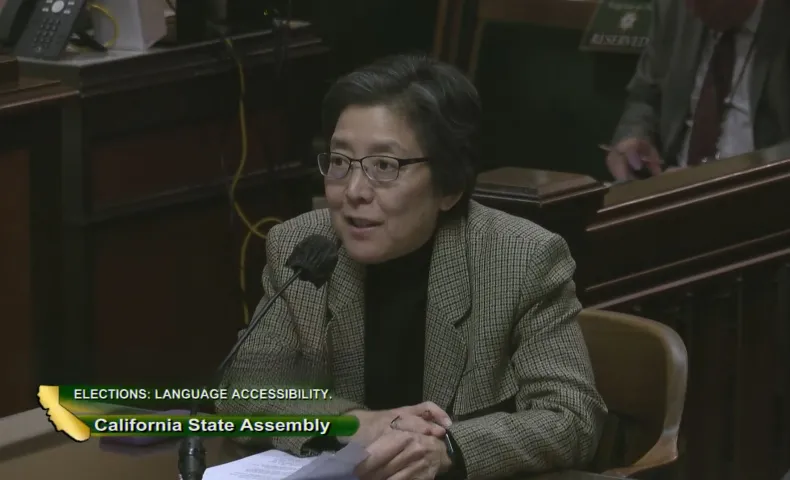

Grantee Spotlight: Deanna Kitamura of Asian Americans Advancing Justice - Asian Law Caucus

Deanna Kitamura is a longtime California civil rights attorney and has been a leader over the last decade in working to expand voting rights and strengthen election systems to be more inclusive. In addition to being a senior staff attorney, last month, she was named program manager for voting rights with Haas, Jr. Fund grantee Asian Americans Advancing Justice—Asian Law Caucus. Asian Law Caucus was founded in 1972 as the nation’s first legal and civil rights organization serving low-income, immigrant, and underserved Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. In her new role, Deanna leads the organization’s work to expand access to the polls for all Californians, whether they speak English, Spanish, Arabic, Korean, or any one of dozens of languages used across the state. Deanna is also a member of a working group supported by the Fund to explore solutions to expanding access to voting and elections among limited-English speakers.

Fund to explore solutions to expanding access to voting and elections among limited-English speakers.

To mark AAPI Heritage Month, Haas, Jr. Fund Democracy Program Director Raúl Macías recently spoke with Deanna about her life and career in civil rights law, the challenges facing people who use non-English languages when it comes to voting, and solutions for expanding language access for AAPI communities and others.

Q: What motivated you to pursue a career in civil rights law?

Deanna Kitamura: My mom was an immigrant from Japan, and my dad was born in Hawaii but spent most of his childhood in Japan. That affected me in many ways. My mom, who didn’t speak English very well, wasn’t able to interact easily in U.S. society as an immigrant. I think she was marginalized because of that. Asian Law Caucus is part of a workgroup brought together by the Haas, Jr. Fund and we conducted listening sessions in immigrant communities. During the sessions, the participants discussed the lack of access to translated ballots and hurdles to exercising their right to vote. So we’re seeing the trend of marginalization continue to this day.

In addition to witnessing my family’s experience, I learned about historical injustices pretty early. When I was a kid, the mini-series Roots came out. That had a huge impact on me to see what slavery was like at that human level. Later, I learned about the U.S. government’s mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. My parents were in Japan at the time, so that didn’t affect our family directly. But I realized growing up that had I been alive in California during that time, I would have been incarcerated just for being me.

So it was a combination of my family experiences and U.S. history that motivated me to do the work I do. I ended up going to law school specifically to pursue a career in civil rights law.

Q: What are some of the systemic barriers to voting you’re seeing for immigrants and AAPI communities right now?

DK: I think lack of language access is a huge problem. Today, 31% of U.S. immigrants are Asian Americans, and many prefer non-English languages. Even in states like California, voter registration, voter guides, and ballots are not translated in many languages even though there is a need. That means there are big language barriers to accessing the ballot and a lack of understanding of our electoral system. Combine all of that, and it keeps you on the outside of political and civic life.

But that doesn’t mean people don’t want to be more active in their democracy. Earlier, I mentioned our language access workgroup and the listening sessions we conducted. We held seven listening sessions across the state in six languages and found that people are hungry for election information. That’s not surprising, and it corroborates other work that shows one cause of low voter turnout in many Asian American communities is the simple fact that they don’t have equal access to information1, and there’s very little outreach to them from election officials and political campaigns. If you’re not reaching low-propensity voters (voters who don’t have a track record of voting consistently), they’re going to remain low-propensity voters.

Q: How can we increase language access for these voters?

DK: We need state and federal laws that require votable ballots and other information in more languages, including those used by smaller and growing populations in California and the U.S. We also need more bilingual poll workers who can help people at polling sites. A 2015 study confirmed what we’ve known anecdotally—language assistance increases Latino voter registration and Asian American turnout.2

At the Asian Law Caucus, we have the largest poll monitoring project in Northern California. We focus on language access, and we also work with Disability Rights California on access for people with disabilities. And we regularly see how our monitors are able to intervene and make sure translated materials are out, and that people can find their poll sites and have easy access to voting.

The challenge is to keep track of diverse and ever-changing populations in communities across the state and to make sure they have what they need. As someone who is deep into these issues, even I struggle to keep up with the vast diversity of California communities and the languages they speak.

So, we work at the local level and also at the state level on policy issues to try to include language access requirements. For example, when the California Voter’s Choice Act3 was negotiated, we insisted that each voter center provide language assistance in every language covered in the county even though state law focuses on assistance at specific precincts within a county. It’s a combination of poll monitoring, local advocacy, litigation, and policy changes that are making the difference in improving language access in California.

Q: Your work is focused primarily on AAPI communities, but you and your colleagues also do a lot of work hand in hand with Black and Latino groups. How do you see your work on these issues as a way to further cross-racial solidarity?

DK: Our language access working group is a great example of working across cultures. We have people and groups at the table that are working in Latino, AAPI, and other language-minority communities. And that’s really important because these issues and these problems cut across so many racial and cultural lines. It’s important to have everybody on board. To only focus on language access for one community doesn’t make sense. It should be language access for all.

And when we work on redistricting, it’s the same thing. The redistricting collaboratives we were a part of were multiracial. We wanted to make sure we were developing district line proposals with all of the different communities too often silenced by politicized redistricting and gerrymandering.

Q: Who have been some of the greatest influences or mentors to you and your work?

DK: History has been my greatest influence. I remember taking a civil rights class in college and reading about regular people who were part of the civil rights movement—the people in the Montgomery bus boycott and the Freedom Riders, or the people marching from Selma to Montgomery. To learn how regular people instigated and made movements happen inspired me. It told me that I could be part of the solution too.

And then in my first summer in law school I worked at an organization called Equal Rights Advocates in San Francisco. There, I was able to see women lawyers making a career out of being civil rights attorneys. Before that, it was just this pipe dream. But then, seeing them be able to do it gave me the confidence to know that I could do this.

Q: What advice would you give to young Asian American lawyers interested in pursuing a career in civil rights law?

DK: If you’re already working at a firm, I would start doing a lot of pro bono work. Many organizations, including the Asian Law Caucus, have longstanding partnerships with private law firms, and they work with us all the time. Working on civil rights law may not be the path to a lavish lifestyle, but if you want a life that is rewarding and has meaning and if you want to add value to society, it’s definitely worth pursuing. And you are surrounded by wonderful colleagues who are trying to improve the world as well.

For an attorney who is interested in voting rights, I’d say that this is a crucial time. Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial group in the US. And the biggest threats to our democracy right now, from voter suppression to misinformation, often target Asian Americans as well as other communities of color. We need more advocates at the table working on these issues and protecting voting rights and expanding language access.

Q: What’s your message for funders about supporting work in this area?

DK: We are at a crossroads right now. Democracy has been attacked; it’s being attacked every day. I know that many funders think California is doing just fine on these issues, especially compared to other states, but thousands of people aren’t able to fairly cast their ballots, elect candidates who will fight for their interests, and get involved in civic processes because of outdated laws, discrimination, and under resourcing in Black, Asian, Latino, and Indigenous communities. And California is also an incubator for new policies and procedures. We’re the largest state, and when we take steps to create a stronger democracy, other states take action too.

The Haas, Jr. Fund is a supporter of the Asian Americans Advancing Justice—Asian Law Caucus. Learn more about AAAJ-ALC, its work to advance voting rights, and how you can get involved here.

1 Language barriers are self-reported as a reason Latinos and Asian Americans do not vote. United States Census Bureau, 2020 Current Population Survey Voting and Registration Supplements.

2 Bernard L. Fraga, Julia Lee Merseth, Examining the Causal Impact of the Voting Rights Act Language Minority Provisions (July 11, 2015).

3 California Elections Code Section 4005.