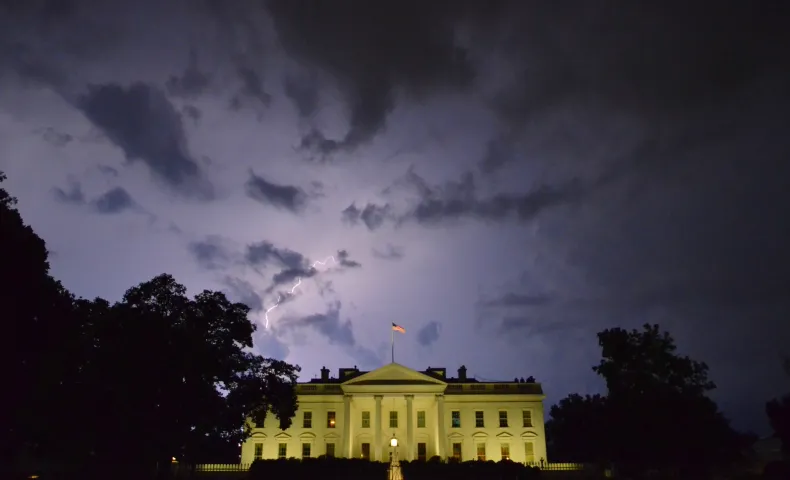

Photo by Amanjeev

Photo by Amanjeev

Philanthropy in the First 100 Days

This article by Aaron Dorfman, Cathy Cha, Jacqueline Martinez Garcel, and Lateefah Simon was originally published in the Chronicle of Philanthropy.

The end of the Trump administration’s first 100 days offers an opportune moment to assess philanthropy’s response to the cultural and political changes buffeting the country.

In the wake of the 2016 election, many people are fearful about a rising tide of animosity and harmful policies across the land. If the marches and other protests we’ve seen reveal anything, it’s that Americans see their basic rights and opportunities are under threat, along with critical support from the federal safety net.

For those of us in philanthropy, all of this begs an obvious question: What are we doing—and is it enough?

The four of us recently participated in a debate during the Northern California Grantmakers’ annual conference about how well philanthropy has responded to the challenges arising in no small part from an election result few foundation officials anticipated. We presented dozens of examples of how grant makers are creatively stepping up. Still, in a vote at the end of the debate, more than two-thirds of the nearly 400 attendees said philanthropy’s response has not been sufficient.

Time and again in our nation’s history, philanthropy has demonstrated its power and potential to help solve urgent problems and ensure that the United States lives up to its democratic ideals. This could be another of those times.

Here are five questions we all can consider as we think about how to respond to the current moment:

Are we dedicating serious money so grantees have the resources they truly need?

In communities across the country, a wide range of organizations are working on the front lines to tackle harmful policies and blunt their impact on those who are most vulnerable. These include well-established organizations that pursue legal and other remedies as well as grass-roots groups that work to mobilize and organize people to advocate and protest.

Dozens of grant makers have created dedicated pools of money to increase the resources available to nonprofits. For example, the California Endowment announced in December that it was creating a $25 million fund to protect health and safety programs in light of threats to the Affordable Care Act.

Other large foundations announcing stepped-up support include the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ($63 million for climate change, reproductive rights, women’s health, and democracy) and the Open Society Foundations ($10 million to fight hate crimes). The Rockefeller Brothers Fund increased its grants budget by 12 percent “to protect and strengthen the vitality of our democracy.”

Small grant makers are getting into the game, too. The Meyer Memorial Trust provided supplemental general-operating grants of $20,000 each to five community-based groups on the front lines of ensuring equal rights in Oregon. Similarly, the Graustein Memorial Fund in Connecticut launched a new effort after the election to support communities threatened by hate and bias.

Some community foundations are stepping up as well. The Brooklyn Community Foundation, the California Community Foundation, and the New York Community Trust (in partnership with the New York Foundation) each put up about $1 million to protect immigrant rights and health care. In Washington, D.C., the Meyer Foundation and the Community Foundation for the National Capital Region announced the Resilience Fund to support nonprofits helping vulnerable people affected by changes in federal policy.

Yet, as terrific as these commitments are, they’re a drop in the bucket compared with the immense philanthropic resources our organizations possess, and compared with what’s needed to mount a sustained and effective response. Philanthropy’s financial response is also dwarfed by potential federal budget cuts and the harm they will bring to many people our field seeks to aid.

Are we investing in building the power of people of color and women?

In an increasingly diverse society, foundations can stand as models for how to invest in building power among people who have too long been disenfranchised and ignored.

This is a time to consider increasing our investments in institutions led by women and people of color and in efforts to bring more of the people most affected by structural and institutional racism into the leadership of our movement for social change. As the country’s demographics continue to shift, it is critical that foundations take stock of who, not just what, we’re investing in.

Whether they focus on education, health, housing, or criminal justice, organizational efforts led by people of color need to be central to our investment strategies, and we must do our part to ensure those on the margins have the long-term support they need to build power and lead efforts for lasting change.

Are we moving money quickly?

Responding rapidly doesn’t come naturally for most foundations. We all have policies and processes in place for reviewing and approving requests and proposals and for getting funds out the door. Many grant makers are cautious about protecting their organizations by limiting what grantees can and cannot do with the funds they receive.

But nonprofit groups that are working to fight harmful policies and protect communities from today’s rapid-fire threats can’t wait. They need money quickly—and with few restrictions—so they don’t miss a beat in their efforts to meet a surge in need and demand. A slow response from a grant maker could mean a missed opportunity to make a measurable difference.

This is why the San Francisco Foundation, the Astraea Foundation, the Women’s Donor Network, and Solidaire have all announced rapid-response funds to react to the urgent needs of frontline resistance organizations.

Among other examples:

The California Wellness Foundation awarded a series of grants in less than eight weeks to help local nonprofits, including trusted and well-connected community foundations, invest in community organizing, meet immigrants’ needs, and provide management support for organizations facing down hate and discrimination. The David Rockefeller Fund is learning to make grant decisions in a matter of hours, not days or weeks. It recently approved $40,000 for an Earth Day climate march just two hours after receiving the request. Kresge Foundation trustees gave the grant maker’s president increased authority to approve discretionary awards so it can respond swiftly to grantee needs and opportunities.

Are we stretching to meet the needs of the moment?

Most foundations award grants only to groups working on certain issues or causes. If there ever was a time to broaden our vision of what we’re about and what we want to achieve, it is now. The threats communities face today touch on issues from education and health care to jobs, civil rights, the environment, and more.

If we stay in our silos and only support those organizations and campaigns that closely match our program requirements, we will probably miss opportunities to make a bigger difference.

Stretching means thinking more expansively about our mission and our vision to respond to the needs of communities we care about. It means following the lead of the Rosenberg Foundation, which recently made its first set of grants to Muslim community organizations. And then there is the Barr Foundation, which normally funds in the areas of climate change and education but has stretched and made 36-month grants to defend the civil rights of vulnerable groups and invest in nonprofit journalism. Similarly, the Omidyar Network recently announced it would invest $100 million in investigative journalism, protecting freedom of the press, and fighting misinformation. It’s the largest investment of its kind to date.

Are we using our voices to defend people most at risk?

Foundations wield an immense amount of influence. Historically, most grant makers have been reluctant to speak out or to raise their profile on urgent issues, but there are times when our voices and our involvement are essential. We need to stand up for people and communities whose rights and opportunities are at risk, or who are being singled out for unjust and hateful treatment.

Within days of the election, the Minneapolis Foundation supported “Sambusa Sunday,” which was organized by the Coalition of Somali American Leaders to counter anti-Muslim sentiment. The foundation saw this as a way to signal its strong support of full inclusion for Somalis in its city.

In other examples, more than 200 foundation leaders signed a joint statement to oppose President Trump’s executive orders on immigration and refugees, and technology companies and their philanthropic arms spoke out strongly in opposition to the administration’s proposed travel ban.

The Wallace Global Fund offered a different model for speaking out: The grant maker recently fired its law firm, which also represents the new president. The fund made public a four-page letter explaining how the firm’s work for Mr. Trump is inconsistent with its values and with core democratic principles.

Standing up in these ways will make many of us uncomfortable, but it is critical, particularly in smaller towns and rural communities where those most in need may have fewer supporters. To the extent that we raise our voices for justice and fairness, it will bring us closer to the people we seek to serve.

Philanthropy has an important role to play in building the kind of society in which we all want to live. Are we acting boldly as our country stands at a crossroads? Are we breaking from business as usual? Are we doing enough when so much of what we collectively believe in is at stake?

These are questions we all are grappling with. Some foundations have taken admirable and inspiring steps since November. But with 100 difficult days behind us and many more to come, it’s time for all of philanthropy to think about how we can truly make a difference for the nonprofits, the communities, and the movements we support.

Aaron Dorfman is chief executive of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy. Cathy Cha is vice president of programs at the Evelyn and Walter Haas, Jr. Fund. Jacqueline Martinez Garcel is chief executive of the Latino Community Foundation. Lateefah Simon is president of the Akonadi Foundation.